Sometimes, when suffering writer’s block, I like to put my mind on a different project to clear out my brain and let ideas percolate. One of the best ways for me to do that and still feel like I’m accomplishing something when I’m on a deadline is to write little bits of flash fiction about other characters in my current WIP. I wrote a ton of these for Sideshow. Some of them may find their way into larger works in the future, but for the time being, I’ve decided to share a few of my favorites with you.

Della Adamson. Act One. A New Beginning

Della kept her eyes closed as the train left the station. She had no desire to have a last look at Montgomery, West Virginia as it faded away behind the train. Years ago, when she had been a little girl, Montgomery had been everything to her. It had been the “big city” and the people who came from there had been interesting and sophisticated. Now, she understood just how small it was. Sure, it was larger than where she grew up, a town that had been named for a kind of coal that hadn’t been profitable for over 100 years, but still, Montgomery wasn’t an escape. Not even Morgantown, the city printed on her ticket, was a true escape. She felt strained and confined by the entirety of West Virginia, the United States, the planet earth. She needed to get away, though she couldn’t say why, and where to was nothing more than a dream.

She had been in school when it happened the first time. Miss Hawthorne, the fresh out of Glenville State, and not all that much older than Della herself, algebra teacher, had been explaining the quadratic equation, and Della suddenly felt unable to breath. Her heart pounded so hard that she could hear it in her ears and her mouth grew dry.

“Is something wrong, Miss Adamson?” Miss Hawthorne had asked sternly, and Della became instantly aware that she had slumped from her desk.

Getting to her feet and brushing off her skirt, Della shook her head. “No, Miss Hawthorne. Just a dizzy spell.” A red flush of embarrassment gathered in her cheeks.

“Do you need to see the nurse?”

For a moment, Della scanned the room trying to decide what to do. All of her classmates eyes were on her. Usually, she appreciated the attention, but this time the whole thing made her feel profoundly uncomfortable. She tried to take a deep breath, but her lungs felt too small. “I suppose,” she whispered, trying to sound poised, despite how she felt inside.

Elegance in all situations, her mother often repeated. Della tried her best to replicate this. Usually it was her temper that got the best of her, but this time, she felt sick. She needed desperately to lie down, and could have done so right there in the classroom, but she refused to allow something as small as illness make her appear anything less than the refined lady her mother had always taught her to be. She excused herself from the room and did not allow the dizziness to overtake her again until she had finally made her way into the hall. Instead of going to the nurse, she walked out of the school and went directly home.

The attacks came with regularity after that. There appeared to be no pattern to them. Della would find herself overcome at town social events, at the meat counter of the deli, in aisle of the general store, at night before she went to bed, and in the morning as she readied coffee for her father and older brothers before they left for work. She began to feel constantly suffocated and never seemed able to take a full breath. She decided then and there that the only way to solve the problem was to leave.

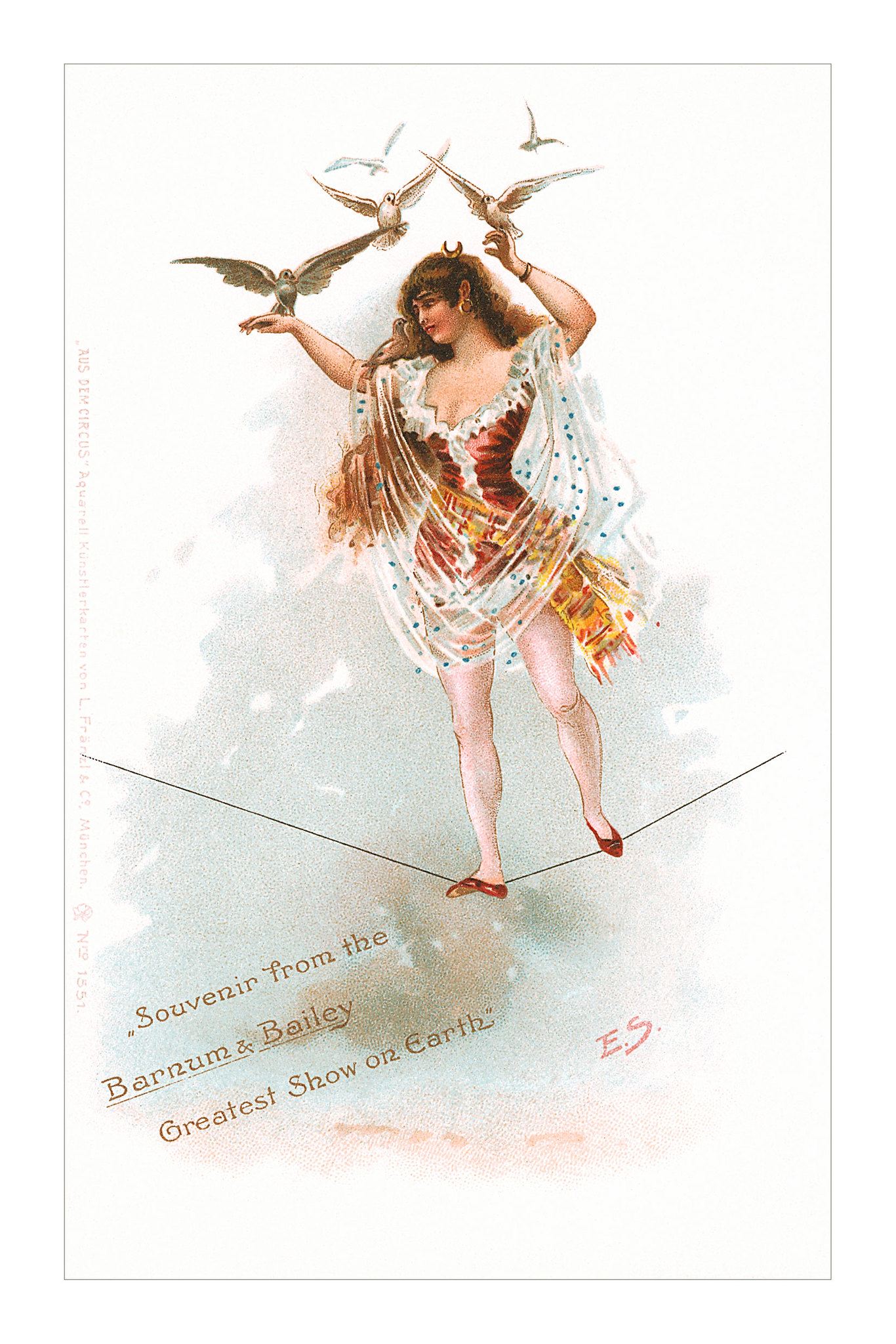

After she felt that a sufficient amount of time had passed, she pulled a small battered brown leather suitcase from under the chair in front of her and snapped it open on her lap. Inside she had packed everything in the house that had belonged to her: a few changes of clothes, a string of pearls, a pair of red kitten heels, two battered Agatha Christie novels with creased and folded covers, and, hidden underneath it all, an old photograph of her mother in a tarnished silver frame. She took the photograph out now and examined it. It had been taken many years before Della had been born, before her mother had even met her father. She wore a tight fitting leotard and a long flowing skirt with a slit up to her mid thigh. Mrs. Belinda Adamson didn’t dress like that anymore. She would have been scandalized for Della to even consider wearing such an outfit. Still, there she was, looking proud as could be, and standing on a small, obviously swaying wire. The faces were too similar. She may have aged, but there was no denying that the woman in the picture and Della’s mother were one and the same. As a young girl the picture had perplexed Della, until she had eventually, piecemeal, worked its backstory out of the now austere woman.

of her mother in a tarnished silver frame. She took the photograph out now and examined it. It had been taken many years before Della had been born, before her mother had even met her father. She wore a tight fitting leotard and a long flowing skirt with a slit up to her mid thigh. Mrs. Belinda Adamson didn’t dress like that anymore. She would have been scandalized for Della to even consider wearing such an outfit. Still, there she was, looking proud as could be, and standing on a small, obviously swaying wire. The faces were too similar. She may have aged, but there was no denying that the woman in the picture and Della’s mother were one and the same. As a young girl the picture had perplexed Della, until she had eventually, piecemeal, worked its backstory out of the now austere woman.

The picture had been taken during her days as a circus aerialist. She had been born into a family of them and had been trained, along with her brothers and sisters, to perform acrobatic feats of daring high above the crowd, much to their awe and delight. At the time, Della had found the tale almost as impossible to believe as the thought that her mother would have ever worn such an outfit. It boggled the mind to think of her mother, whose long limp grey skirts practically always touched the floor, who always told Della to never draw attention to herself, performing in a circus. Everyone who knew Belinda Adamson knew her to be a taciturn woman with a melancholy streak a mile wide. She was the sort of woman who faded swiftly and easy out of a stranger’s memory. She didn’t seem like the sort at all. However, as time went on and Della watched, she became clued into small hints that the story was true after all. For one thing, her mother had amazing reflexes. If one of her brothers dropped a glass, she could catch it from halfway across the room.

“Do you know how expensive these are?” She would admonish in a stern voice.

For another, she had a strength that her small frame did not even begin to imply. She could lift the beds to vacuum under them and maneuver heavy buckets of milk all the way up from the store because the milkman did not come far enough up the mountain to deliver them. It did begin to give Della pause.

Her sister, she had told Della one day, when feeling charitable to her questions, had managed to stay in the business even after the Depression had shuttered a good three-quarters of the shows in the country. She had said it with such disdain that Della could easily see she did not approve of this choice, but it struck Della as an odd thing to look down one’s nose about. It wasn’t like her mother had chosen a particularly lucrative profession either, marrying a miner and having his five-boy-one-girl brood. In fact, she thought this mystery aunt probably had a far better measure of things than her mother did.

She tucked the picture away, thinking now of that aunt, trying to remember her name. Christina? Or was it Elina? Sophie? She wasn’t sure. All she knew was that she taken up working with an Irishman named McClure, who ran a traveling carnival. Her mother had talked about her siblings so rarely and under so much duress that it was possible, Della thought, that she had even this wrong. She shook her head and tucked the photograph away, snapped the suitcase shut, and tucked it back under the seat in front of her. She would have time to worry about the next step when she reached Morgantown, where a carnival called McClure’s Amusements was camped out for a weekend.

She would miss her mother, but more than anything she needed to breath.